On April 8, 2022, a Tochka-U short-range ballistic missile struck the main railway station in Kramatorsk in the Donetsk region of government-controlled Ukraine. The missile killed at least 50 people, including five children. Civilians had gathered at the station to flee the approaching Russian offensive, which has pivoted to the country’s east in recent weeks.

A recent BBC report stated it had found “clear evidence” that the missile which struck the station had a cluster munitions warhead.

Russian officials have blamed the strike on Ukraine, citing claims that the Russian military does not use the Tochka-U. Pro-Russian media cited other assertions relating to the missile’s serial number, and a hypothesised flight path of the missile.

Bellingcat, and others in the open source community, have cross-referenced these claims with publicly available footage in an attempt to establish the origin of the Tochka-U missile that took dozens of lives at the Kramatorsk railway station on April 8.

At the time of writing, the available open source evidence remains insufficient to reveal all details about the strike, including the direction of origin of the missile. However, it does appear to debunk a central argument by the Russian state in its defence: that its military does not operate the Tochka-U missile system.

Social media images and videos as well as Russian news reports from 2021 show the country’s forces displaying Tochka-U launchers, while satellite imagery from February 2022 seems to depict military vehicles consistent with the appearance and dimensions of the launchers at a base in south-western Russia. Experts Bellingcat spoke to also said that even though Russia has reportedly phased out the Tochka-U missile in recent years, that doesn’t render Russia’s stock of the weapons inoperable or mean they cannot still be deployed. Amnesty International, meanwhile, stated that a Tochka-U missile was used by Russia in Donetsk on 24 February 2022.

Before the Attack

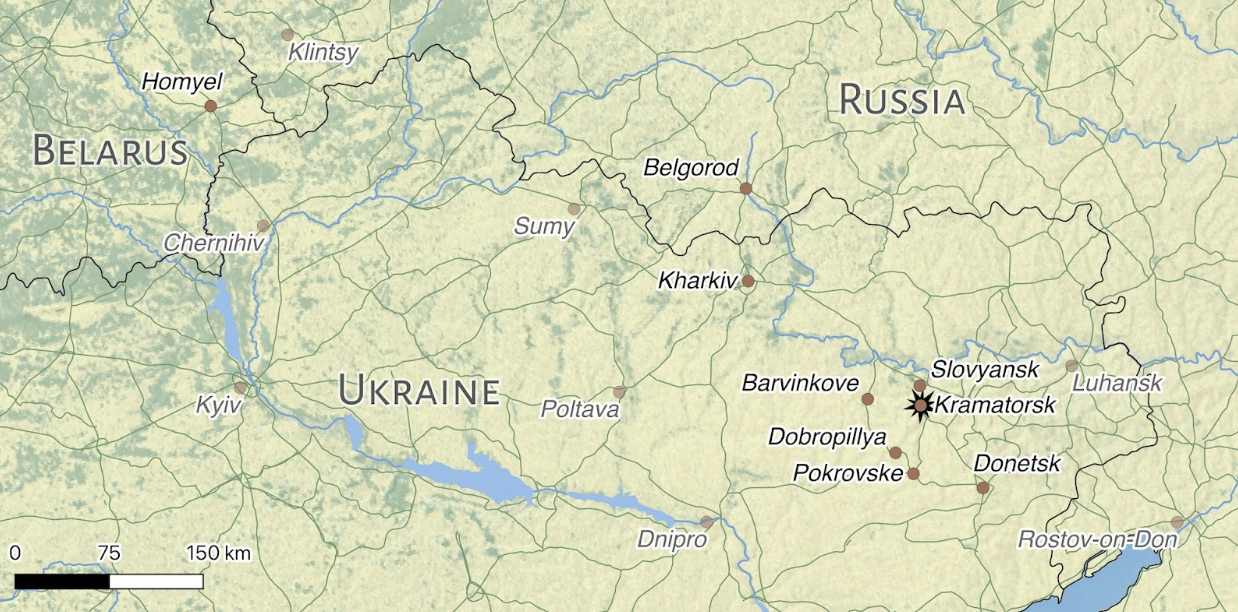

On April 7, the day prior to the strike on the Kramatorsk station, the chairman of the board of the Ukrainian railroads Oleksandr Kamyshin wrote on Telegram that a Russian airstrike at Barvinkove station in the neighbouring Kharkiv region had blocked trains evacuating civilians from Slovyansk and Kramatorsk. Later that night, Kamyshin reported that the obstacle had been cleared and that the affected trains were able to complete their journeys.

That same day, a popular Russian pro-war Telegram channel advised civilians evacuating the two cities against travelling by rail, likely in light of the air strike.

On the morning of April 8, at 10:13 am Kyiv time, the Russian Ministry of Defence claimed in a Telegram post that it had carried out “air-based” missile strikes against materiel for Ukrainian military reserves arriving at Pokrovsk, Slovyansk and Barvinkove railway stations. In the minutes that followed, local Telegram channels in non-government controlled areas of the Donetsk region were flooded with footage of missile launches.

Less than 20 minutes later, reports emerged that Kramatorsk was under fire. By 10:44 am, Kamyshin announced on his Telegram channel that two missiles had struck the Kramatorsk railway station.

At 11:01 am Dmitry Steshin, a correspondent for the pro-Kremlin tabloid Komsomolskaya Pravda, posted a video to his Telegram channel adding that explosions had been heard 10 minutes prior at the Kramatorsk railway station, apparently targeted at a large group of Ukrainian soldiers. The fact that Steshin deleted the post shortly afterwards did not go unnoticed by journalists.

It seems implausible that Steshin, widely known for his strongly pro-Russian positions, could have filmed the video himself in a city then under Ukrainian control. Nevertheless, the video he uploaded and the caption he added were widely shared by pro-Kremlin Telegram channels. As Russian independent news outlet MediaZona noted, these posts can still be found online.

An hour later, the Russian Ministry of Defence (MoD) denied any culpability. Its statement emphasised that the missile found in Kramatorsk was a Tochka-U — a type which it claimed Russia did not operate. Steshin also made this claim on his Twitter account, alleging that the Russian military had not used the Tochka-U for 30 years.

In an updated statement, the Russian MoD later claimed that the Ukrainian 19th Missile Brigade had fired the Tochka-U missiles at Kramatorsk from Dobropillya, a town to the southwest of Kramatorsk.

The statement also insisted that open source videos showing Russian-operated Tochka-Us in fact showed the same model of missile operated by the Belarusian military during joint Russian-Belarusian exercises leading up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. However, other open source evidence appears to contradict this.

This is not the first time that Russia has denied operating the Tochka-U missile system. On March 16, two days after a missile struck the centre of Donetsk, Russia’s mission to the UN also denied that its military used the weapon.

The Tochka-U Question

The Tochka-U missile plays a central role in the Russian authorities’ insistence that their armed forces could not possibly have been behind the missile strike on Kramatorsk. Namely, they insist that the Russian military has phased out use of this ballistic missile.

These claims are seemingly in line with a recent modernisation drive for Russia’s military. In June 2020, state media website Interfax reported that the entire Russian military had updated its missile systems, replacing the Tochka-U with the more modern Iskander.

Scott LaFoy, Director of Nuclear and Technology Security Programs at Exiger Government Solutions, who has spent his career as an open source analyst focusing on ballistic missiles and nuclear weapons systems, told Bellingcat that Russia “didn’t exactly throw them all in a river” when describing what it may have done with the leftover Tochka series.

“We’ve seen legacy equipment deployed by Russia before, and Tochka-Us are valuable munitions that can offset expensive Iskander costs, allowing Russia to burn legacy inventory instead of purely new, expensive munitions”, he added.

Open source evidence also indicates that Tochka-U missiles have been spotted on several occasions during the invasion of Ukraine.

According to the Conflict Intelligence Team (CIT), a reporting partner of Bellingcat, a train loaded with Tochka-U launchers and loader vehicles (based on the BAZ 5921 and 5922 chasses, respectively) moved from Homyel in Belarus to the Russian city of Belgorod in late March. CIT cited a March 30 video which was posted to Twitter by the prominent user GirkinGirkin, showing the launchers being transported by train.

This would be in line with the ongoing Russian retreat from the Kyiv front and consolidation in the east. The vehicles were marked with ‘V’ tactical marks, which are used by the Russian armed forces involved in the war against Ukraine. The Belarusian military, which has not formally entered the war, is not known to use these markings.

The Hajun Project, a group of anonymous Belarusian researchers, posted images of these same vehicles on Twitter on March 18. The team claimed that the launchers had arrived in Belarus’ Minsk region on a Russian Air Force An-124 as an additional batch to supplement Russian Tochka-Us which had already arrived earlier in the month. Bellingcat was unable to independently verify this claim.

In the March 18 pictures, the vehicles did not yet have their ‘V’ tactical marks and still had their original numbers painted on. Judging by their similar wear and camouflage patterns, these vehicles appeared to be the same as those seen heading towards Belgorod by railway.

Источник: https://www.bellingcat.com/